At the height of the wave of kidnappings of the sixties, in the United States, an airplane was hijacked on average every six days.

This week, 50 years have passed since Raffaele Minichiello carried out, as reported at the time, the hijacking of a “longer and more spectacular” aircraft of all.

August 21, 1962

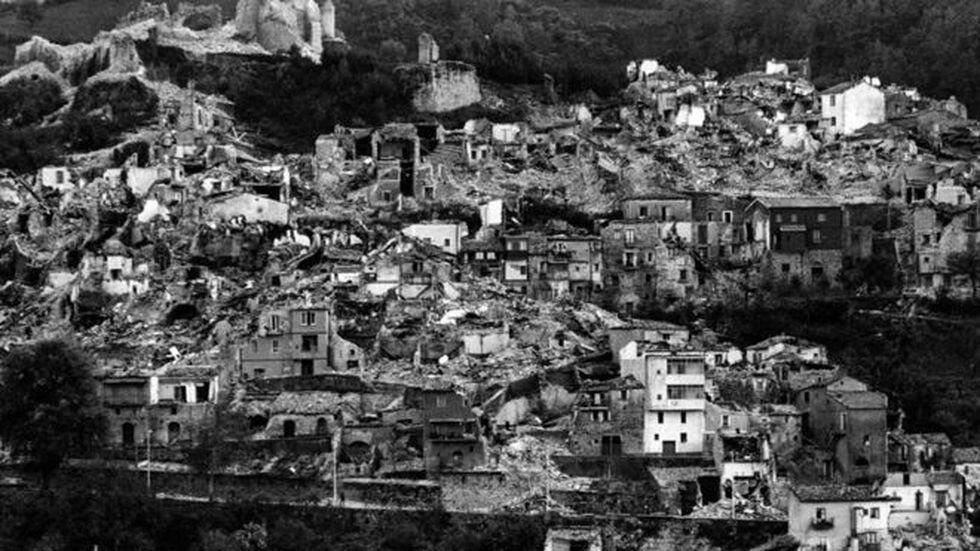

Under the hills of southern Italy, northeast of Naples, a fault broke and the earth began to shake.

Those who lived on the surface, in one of the most earthquake prone areas in Europe, were used to it.

The 6.1 magnitude earthquake in the early hours of the night was enough to scare everyone, but it was the two powerful aftershocks that caused the greatest damage.

At 20 km from the epicenter, the Minichiello family lived, including Raffaele, who was then 12 years old.

By the time the earth stopped shaking, its town, Melito Irpino, was uninhabitable. The family was left with nothing and no person in a position of authority approached them to help them, Raffaele recalls.

The damage was such that almost the entire town was evacuated, and later the city was rebuilt. Many families returned, but the Minichiello decided to leave for the US. In search of a better life.

But what Raffaele Minichiello found in his new country, on the other hand, was war, trauma and bad reputation.

01:30; October 31, 1969

Dressed in camouflage, Raffaele Minichiello boarded the plane in Los Angeles with a ticket of US $ 15.50 in hand bound for San Francisco.

This was the last stop on Trans World Airlines Flight 85 that had left Baltimore several hours ago, before making a stop in St. Louis and Kansas City.

The crew was composed of three pilots in the cabin, accompanied by four young hostesses , most of whom had begun work a few months earlier.

The most experienced was Charlene Delmonico , a 23-year-old girl from Missouri who had been flying with the company for three years.

Delmonico had changed his turn to fly in the TWA85, since he wanted to be free during Halloween night.

Before leaving Kansas City, Captain Donald Cook (31) informed the flight attendants of a small change: if they wanted to enter the cabin, they should ring a bell on the side, instead of knocking on the door.

The flight landed in Los Angeles late at night. Some passengers got off, while others got on to make the short trip to San Francisco.

The hostesses began to check the tickets of those who joined the flight. But Delmonico was struck by one of the new passengers, especially for his bag.

The young tan dressed in camouflage and with his wavy brown hair hairstyle seemed somewhat nervous upon entering, but he was kind. A thin container was peeking out of his backpack.

Delmonico went to the first-class compartment, where his colleagues Tanya Novacoff and Roberta Johnson guided the passengers to their seats.

“What was it that stood out from the young man’s backpack?” He asked his companions. The answer – a fishing rod – reassured her, and she returned to the back of the aircraft.

The flight was not full. With only 40 people on board, there was room for everyone to look for a line in which to stretch and sleep.

Among the passengers were members of the pop band Harpers Bizarre, who after two years of his last hit (an adaptation of a theme by Simon & Garfunkel) would reach the peak of his fame a few hours later.

Guitarist Dick Scoppettone and drummer John Petersen sat comfortably in their seats on the left side of the plane and lit their cigarettes.

It was 01:30 on Friday, October 31, 1969. 15 minutes after the TWA85 flight from Los Angeles to San Francisco began, the kidnapping began.

With the lights low so passengers could rest, Charlene Delmonico began tidying up the kitchen in the back along with her colleague Tracey Coleman, a 21-year-old girl who had started working at TWA 5 months ago.

The nervous and camouflage passenger approached the kitchen and stood beside them both. He had an M1 rifle in his hand. Delmonic, calm and professional, simply replied: “You shouldn’t have that.”

He responded by giving him a 7.62mm bullet to show him that he was loaded, and ordered him to drive him to the cabin to teach the crew.

The movement down the hall woke Dick Scoppettone. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Delmonico followed by a man who aimed her from behind with a rifle.

His partner John Petersen looked at him stunned from a few rows later.

One of the passengers sitting behind, Jim Findlay, stood up to confront Minichiello. He turned and shouted to Delmonico: “Stop!”

“This man is a soldier,” the flight attendant thought.

The young man sent Findlay to sit down and approached along with Delmonico to the cabin.

“There is a man behind me with a gun,” the flight attendant told her companions who quickly stepped aside as they both walked down the hall behind the curtain of the first-class compartment.

Some passengers heard Minichiello yell at Delmonico as he became more nervous as he approached the cabin, but most of the time he behaved in a kind and respectful manner.

When the door opened, Delmonico informed the crew that there was a man behind her with a gun.

Minichiello entered and aimed the three men with his rifle: first at Captain Cook, then at co-pilot Wenzel Williams and flight engineer Lloyd Hollrah.

Minichiello seemed well trained and well armed, Williams thought. He knew what he wanted from the crew and was determined to get it.

After Delmonico left the cabin, Minichiello addressed the three men and, in an English with a strong foreign accent, said: “Turn to New York.”

The unusual image of a man walking on the plane with a gun did not go unnoticed by the rest of the passengers who were still awake.

The members of Harpers Bizarre quickly sat side by side as they wondered how the man had been able to enter the plane with a rifle.

Nearby was Judi Provance, a TWA flight attendant who was not working that day. He was returning home in San Francisco. Every year, she and other TWA employees participated in training on how to respond during emergencies, including kidnappings.

The most important thing they taught him was to remain calm and not sow panic. Another lesson was not to catch the kidnapper: they told him that it was easy for him to awaken the compassion of the crew.

Provance mentioned quietly to those around her that she had seen someone walking down the hall with a gun.

Jim Findlay, the man who had tried to intervene before, was also a TWA pilot, although he was traveling as a passenger. He checked the kidnapper’s bags to discover his identity and make sure there were no more weapons on board.

Captain Cook’s voice was heard by the speaker: “We have a very nervous young man here and we will take him wherever he wants to go.”

As the plane moved further and further away from San Francisco, other messages were communicated to passengers, or began to circulate: they were going to Italy, Denver, Cairo, Cuba.

The crew inside the cabin feared for their life, but some passengers lived what was happening as part of an adventure . Rare, but adventure, after all.

It was not uncommon for people aboard the TWA85 to think they were going to Cuba. For a long time it was the kidnappers’ favorite destination.

Since the early 1960s, several Americans disillusioned with their homeland and tempted by the promise of a communist ideal fled to Cuba after Fidel Castro’s revolution.

Since American planes didn’t normally fly to the island, kidnapping was a way to get there.

And accepting US hijackers, Castro could embarrass and annoy his enemy while demanding money for the return of the plane.

A period of three months in 1961 announced the beginning of the phenomenon of kidnapping.

On May 1, Antulio Ramírez Ortiz got on a National Airlines flight in Miami with a false name and took control of the aircraft by threatening the captain with a kitchen knife.

He demanded that he be taken to Cuba, where he wanted to warn Castro of a plot to kill him, who had been totally imagined by him.

Two other kidnappings followed the following months, and in the 11 years that followed, 159 commercial flights were hijacked in the US , explains Brendan I Koerner, in his book “The Skies Belong To Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking. “

The kidnappings that ended up in Cuba were so common, he writes, that at one time the captains of US airlines were given maps of the Caribbean and guides in Spanish, in case they had to land unexpectedly in Havana.

It was even suggested at some point to build a replica of the Havana airport in Florida, to make the kidnappers believe they had arrived in Cuba.

Kidnappings were possible due to lack of security at airports. The passengers’ luggage was simply not checked because there had never been any problems until the kidnappings began.

And then, the aviation industry was reluctant to introduce checks because they feared this would ruin the travel experience and slow the billing process.

“We lived in a different world,” Jon Proctor, a TWA employee at the Los Angeles International Airport in the 1960s, tells the BBC.

“People didn’t blow planes. In any case, they could kidnap it and take it to Cuba, but they didn’t try to blow it up.”

It was later learned that Raffaele Minichiello had disarmed the rifle and put it in a tube before boarding the plane. Then he had assembled it in the aircraft’s bathroom.

By the time the TWA85 hijack occurred, 54 aircraft hijackings had already taken place in the country in 1969, the equivalent of one every six days. But nobody had made them fly to another continent.

The crew received cross messages from their nervous passenger: he wanted to go to New York, or maybe Rome. If the destination was New York it would be a problem, since there was only enough fuel to fly to San Francisco, so they would have to stop to load more.

And if he wanted to go to Rome, the problem would be even greater: no one on board was qualified to make an international flight.

Finally, Captain Cook was allowed to speak directly to the passengers: “If you have made plans in San Francisco,” he said, “do not think about fulfilling them, because you are going to New York.”

After negotiating, Minichiello agreed to let the captain land in Denver to load enough fuel to reach the east coast . When they flew over Colorado, Cook first alerted the air control tower that the plane had been hijacked.

The plans changed quickly: Minichiello would drop the 39 passengers in Denver, but insisted that one of the flight attendants stay on the plane. The one who stayed was Tracey Coleman.

Minichiello had asked for the lights of the Stapleton International Airport in Denver to go out when the plane landed. He did not want to arouse suspicion, and had promised to free the passengers if no problems arose.

Passengers who got off the plane in the middle of a cold and foggy night were greeted by a serious-faced FBI agent.

The relief of those who came down was evident. They were led by a dark corridor in the terminal where a lot of FBI agents were waiting for them, who had rushed to the airport to take note of the testimonies of the 39 passengers and the three aircraft carriers.

The members of Harpers Bizarre remembered the words his manager had once said to them: if they were in trouble, whatever, they would call him first before contacting the hospital or the police.

They did, and the tactic gave results: dozens of reporters approached to hear their story. “It was the best publicity we’ve ever had, by far,” Dick Scoppettone told the BBC.

After days of interviews, flight attendants returned to their homes in Kansas City, while the news continued to report on the course of the kidnapping.

Delmonico spent a day unable to sleep at home. That night, the FBI called her and the agents asked if they could see her. They arrived at 11 p.m. and showed him a photo.

It was the image of Raffaele Minichiello. “Yes, it’s him,” he said.

It was a face I would see again almost 40 years later.

The flight continued quietly from Denver. Minichiello settled in first class with the weapon at his side, already more calm. He made a drink with two small bottles he found (one of whiskey and one of gin).

Only five people remained aboard the TWA85 – Captain Cook, co-pilot Wenzel Williams , flight engineer Lloyd Hollrah , flight attendant Tracey Coleman and the kidnapper.

The plane landed at John F. Kennedy airport late in the morning, and parked as far as possible from the terminal. The captain’s order, as in Denver, was that as few people as possible approached the ship.

But the FBI was ready and eager to stop the kidnapper before he set the precedent of taking a domestic flight to another continent.

About 100 agents were waiting for TWA85, many disguised as mechanics, hoping to surreptitiously get on the ship.

Minutes after landing, when they were about to load fuel, the FBI began approaching the plane.

Cook spoke with an agent through the cabin window, who wanted Minichiello to come talk to them.

“Raffaele was running down the aisles from top to bottom, to make sure no one tried to enter,” Wenzel Williams told the BBC. “He thought he would be shot if he approached the window.”

Without taking an eye off his passenger, the captain warned the agents to get away from the plane. Shortly after, a shot was heard.

The accepted version of the events is that Minichiello did not want to shoot, and that it was an accident.

The bullet pierced the ceiling but did not penetrate the oxygen tank or the fuselage.

But even though it was apparently an accident, he shook the crew and reminded them that their lives were at risk.

Cook – who was sure that the rifle had been fired on purpose – yelled at the agents through the window, and told them that the plane would leave immediately without loading fuel.

Two TWA captains with 24 years of experience and who could make international flights, Billy Williams and Richard Hastings, made their way through the FBI agents and boarded the plane.

“The FBI plan was almost a recipe for the entire crew to be killed,” Cook told the New York Times later.

“We were sitting with that child for almost six hours and we saw how he went from being almost a furious maniac to being a relatively complacent and intelligent young man with a sense of humor. And then those idiots … decide irresponsibly to change their minds on how to handle this child without relying on any information, and all the trust we had managed to build for almost six hours was completely destroyed. “

The two new pilots, who were not in the mood to entertain the kidnapper, took over the plane. Minichiello ordered everyone to stay in the cabin with their hands on their heads.

The plane took off quickly, without enough fuel to reach its destination: Rome.

Twenty minutes after the plane left New York with a bullet housed on the roof, the tension on board had lessened, thanks in large part to the fact that Cook had convinced Minichiello that the crew had nothing to do with chaos at the Kennedy airport.

What happened there meant that the plane could not load fuel, so, within an hour, the TWA85 landed in Bangor, Maine, in the northeastern US, where it loaded enough fuel to cross the Atlantic.

By that time, the history of kidnapping and drama in New York had won the attention of all American media.

Photographers and reporters flocked to Bangor airport.

About 75 policemen made sure that the press was kept as far away from the plane as possible, so that no one could provoke the kidnapper.

Hundreds of people also approached the airport to witness the event.

The kidnapper spotted two people watching from a nearby building. Cook, eager to leave, informed the control tower: “Better hurry up. He says he will start shooting if they don’t leave. ” The two men left immediately.

As the plane headed to international airspace, a sense of solidarity began to grow among those who had been together for more than 9 hours.

But under the surface, even while trying to keep the kidnapper happy, the crew continued to fear for his life.

With the two new pilots on board, Cook went to sit with Minichiello. They exchanged stories. Cook told him about when he first worked as an air traffic controller for the US Air Force.

The rifle remained between the two. No one of the crew tried at any time to take it away , for fear of how it would react.

Minichiello asked Cook several times if he was married and he said yes, despite being single. “I found it smarter,” he told the New York Times later.

He assumed that he was less likely to harm the people of the crew who were married.

“He asked me how many children he had and I told him one. Then he asked me about the others and I said: ‘Yes, everyone is married.'” In fact, only one was.

Tracey Coleman, who was flying outside the US for the first time. or for more than four hours, he also spent time talking with Minichiello.

He showed him card games including the solitaire. He was “a very easy guy to talk to,” he remembers.

He told him how his family had moved to the US, and also that “he had had some small problems with the military in the US and that he wanted to return to his home in Italy,” Coleman later told him. Stewardess, to an aviation magazine.

She slept a little during the six-hour flight from Bangor to Shannon, on the west coast of Ireland, where the TWA85 refilled fuel in the middle of the night.

When the TWA85 crossed time zones as it approached Ireland, and on October 31 it became November 1, Minichiello turned 20 . No one celebrated.

Half an hour after landing in Ireland, the TWA85 set off again on its last 11,000 km stretch to Rome.

The TWA85 flew over the Fiumicino airport in Rome early in the morning. Minichiello had one more request: the plane had to park far from the terminal and had to come to look for an unarmed policeman.

The kidnapping was coming to an end, 18 hours after starting in the sky of California.

It was, as described by the New York Times at the time, “the longest and most spectacular kidnapping in the world.”

In the last minutes of the flight, Williams says the kidnapper offered to take the crew to a hotel, an offer that they kindly declined.

Minichiello feared that they would be punished for not having taken his weapon when they had the chance.

“I gave them a lot of problems,” he told Cook. “Okay,” replied the captain. “We don’t take it as personal.”

At the airport, shortly after 05:00, an Alfa Romeo approached the plane. From there came Pietro Guli, a customs official who had offered to receive the kidnapper.

He walked towards the aircraft with his hands up, and Minichiello went out to meet him.

“I’m sorry I caused you all these problems,” Minichiello told Cook, and noted his address in Kansas City so he could write to him later and tell him what would happen after he broke up.

The two men walked towards the car, Minichiello still with the rifle in his hand. The people on board finally felt a deep relief.

After Los Angeles, Denver, New York, Bangor, Shannon and Rome, there was only one destination left: “Take me to Naples,” Minichiello ordered Pietro Guli. He was on his way home.

Four police cars followed the Alfa Romeo, where the voices of the police were heard with difficulty through the radio. Minichiello, sitting in the back, turned it off and showed him the way.

In the countryside, a few kilometers from the center of Rome, the car continued its journey along roads that became increasingly narrow. Until he reached a point where he could no longer continue and the two men got out of the car.

Realizing that he had few options left, Minichiello panicked and ran.

23 hours after the TWA85 left Los Angeles, Minichiello’s trip had come to an end.

He had to end up with the publicity that the kidnapping had generated.

For five hours, hundreds of police with dogs and helicopters tracked the hills around Rome in search of the kidnapper.

But in the end, it was a priest who found him.

Saturday, November 1 was All Saints’ Day, and the morning mass of the Shrine of Divine Love was full. Among the well-dressed people of the congregation, a man in a shirt and briefs called attention.

Minichiello had sought refuge in the church after having removed his military clothes and hiding his weapon in a barn.

But his face was famous now, and the Vice Chancellor, Don Pasquale Silla, recognized him.

When the police finally surrounded him outside the church, he was puzzled – something the reporters interpreted as the arrogance of a young criminal – that his countrymen wanted to stop him.

“Why are they arresting me?” He asked.

He used the same tone he used hours earlier when he spoke to reporters, after a brief interrogation at the police station in Rome.

“Why did you do it?” One of them asked. “Why did I do it?” He replied. “I dont know”. When another asked him why he had hijacked a plane, he replied in a puzzled voice: “What plane? I don’t know what they are talking about.”

But in another interview, he revealed the real reasons behind his act.

When the news of the arrest of Minichiello began to be known around the world on the afternoon of that same day, Otis Turner was having breakfast at his Marine Barracks in California.

In one corner, the television showed images of the kidnapping and the persecution of its author by the Italian countryside. “Then they showed a picture of Raffaele,” Turner told the BBC.

“I was simply stunned, absolutely stunned.”

The two men had served in the same platoon in Vietnam and became close friends before they were separated in the US.

“At first I was confused,” he adds, “but when I thought about it, I remembered that he had had some problems and it all made sense.”

When the kidnapping occurred, it had been four and a half years since the US combat forces had first arrived in Vietnam, and there were still five years left for the fall of Saigon.

USA He would leave Vietnam after he failed completely in his mission, leaving more than 58,000 US soldiers dead , as well as millions of Vietnamese – both combatants and civilians – dead.

The opposition in the US Against the war it reached its highest point towards the end of 1969. It is estimated that about two million people across the country participated in a march to end the war two weeks before the kidnapping.

It was a month before the lottery was put into practice to recruit young Americans to fight, but many thousands of young people had already volunteered, believing at the time that the cause, fighting the communists of North Vietnam, was valid .

Raffaele Minichiello was one of the volunteers.

In May 1967, the 17-year-old left his home in Seattle, where he and his family had moved after the earthquake in his Italian homeland in 1962.

He traveled to San Diego to enlist in the Marine Corps and, for those who knew him – a bit stubborn and enthusiastic – this was no surprise.

Minichiello barely spoke English and his classmates were teasing him for his strong Neapolitan accent before he dropped out of school altogether. Leaving studies meant the end of his ambitions to be a commercial pilot.

But he was proud of his adopted country and was willing to fight for him in the hope that he would be allowed to become a naturalized American citizen.

Otis Turner arrived in Vietnam at about the same time as Minichiello, and they served in different squads in the same Navy squad.

They were sent to the front line in the jungle for several months to fight the communist forces.

It was one of the toughest jobs, Turner remembers. “We were at temperatures of 49 ° C, in the monsoon season. It was terrible. We saw the worst of the worst.”

Today, Turner remembers with a shame the things that made them do, and how they did them. His mission was brutally simple: enter towns and cities and kill the enemy.

“Since we joined the Marine Corps, everything was basically kill, kill, kill,” he says. “That was all they wanted us to do.”

Of those in the front, Minichiello used to be the one leading the group. This caused him to be involved in shootings that killed close friends and led him to save others who were in danger.

He was awarded the “Cross to Courage,” which the South Vietnamese government gave to those who had shown heroic behavior during the war.

These men had learned to act in a unique way – they were Marines, born to fight – and adapting to everyday life was impossible.

“There was no time to process everything and think about what you had just done, see a professional,” Turner tells the BBC.

“There were a lot of sick people, confused. Raffaele was like that. We were all confused when we returned from Vietnam . “

Turner says that most members of his platoon and that of Minichiello – including himself – were later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The US Department of Veterans Affairs He estimates that up to 30% of all who served in Vietnam suffered PTSD at some time in his life (about 810,000 people).

Raffaele Minichiello was not diagnosed with this disorder until 2008 .

When a group of reporters found Minichiello’s father near Naples – who at that time was suffering from terminal cancer and had returned to Italy – he knew immediately why his son had hijacked the plane.

“The war must have caused a state of shock in his mind,” said Luigi Minichiello. “Before that, it was always healthy.”

Soon another reason emerged to explain his actions. While in Vietnam, Minichiello had been sending money to his Marines savings fund.

He had raised $ 800. But when he returned to California, he discovered that there were only $ 600 in his account. It was not enough to travel to Italy to visit his father who was dying.

Minichiello spoke with his superiors and insisted that they give him the US $ 200 that, in his opinion, they owed him. His superiors ignored his complaints .

Then Minichiello decided to resolve the matter himself, although very awkwardly.

One night, he sneaked into a store at the military base to steal US $ 200 in goods. Unfortunately for him, he did it after drinking eight beers and falling asleep in the store, where he was caught the next morning.

The day before kidnapping TWA85, he had to appear before a martial court at Camp Pendleton but, as he feared going to prison, he escaped to Los Angeles. He took with him a rifle he had registered as a Vietnam war trophy.

Against all odds, Minichiello became a popular hero in Italy, where he was presented not as a troubled armed man who had hijacked a plane with passengers, but as a young Italian who was able to do whatever it took to return to his homeland.

Minichiello faced a trial in Italy and could not be extradited to the US, where he could have been sentenced to death.

In his trial, his lawyer Giuseppe Sotgiu described him as a poor Italian victim in an unacceptable foreign war.

He was tried in Italy only for crimes committed in Italian airspace and sentenced to seven and a half years in prison. The sentence was reduced during an appeal, and Minichiello was released on May 11, 1971.

Dressed in a brown suit, the 21-year-old left the prison near the Vatican where he was received by a crowd of photographers and journalists.

“Are you sorry for what you have done?” Asked one. ” Why should I be? ” He replied smiling.

After that, his future blurred. The promise of a nude modeling career never progressed, nor did the promise of a film producer who wanted to make him a star of Spaghetti Western.

After leaving prison, Minichiello settled in Rome where he worked as a waiter in a bar. He married the owner’s daughter, Cinznia, and they had a son. At one point he had a pizzeria he called “Kidnapping.”

November 23, 1980

The earthquake that destroyed Raffaele Minichiello’s hometown in 1962 was only a precursor. 18 years later, an earthquake of 6.9 magnitude shook southern Italy. Its epicenter was only 32 km from the one that occurred in 1962.

This was the most powerful earthquake to hit Italy in 70 years, and caused immense damage in the Irpinia region. About 4,690 people died and 20,000 homes were destroyed.

Soon after, Italians organized in large groups began arriving in the area to distribute aid. One of them was Raffaele Minichiello.

The 31-year-old man continued to live in Rome, but felt the need to travel to his hometown three times in two weeks to bring help.

His distrust of authority fueled during his years with the Marines never left him. “I don’t believe in institutions, that’s why I help personally, ” he said. “I know well how are people who don’t keep their promises.”

In the ruins left by the earthquake, a more regretful Minichiello than before began to emerge. “I am very different from who I was,” he said. “I’m sorry for what I did to those people on the plane.”

His redemption did not come with the Irpinia earthquake. And his story could have ended in a very different way if his plan for another attack had been implemented, although this plan was much less elaborate than his kidnapping.

In February 1985, Cinzia was pregnant with her second child. After entering the hospital in labor, she and the baby died as a result of bad practice.

Angry and disappointed again by the authorities, Minichiello designed a plan. His target would be an important medical conference on the outskirts of Rome to draw attention to the neglect that had cost his son and his wife’s life.

He organized to get weapons and perpetrate violent revenge.

But while planning the attack, he befriended a young colleague, Tony, who realized that he was not well.

Tony taught him the Bible and read some of his passages aloud. Minichiello listened to him and, over time, decided to dedicate his life to God and abandoned his plan of revenge.

In 1999, Minichiello decided to return to the US for the first time since the attack.

He had learned that there were no pending criminal charges against him in the country, but his decision not to face a martial court did not pass without consequences.

His escape caused a discharge that limits access to his rights as a veteran.

His former platoon companions had been struggling to improve the terms of their withdrawal and reflect their services in Vietnam, but until then they had not been successful.

“Raffaele was a great Marine, a decorated Marine,” his former partner Otis Turner tells the BBC. “He was the guy who was always in the front. He volunteered for everything. He saved lives. What he did for his country, his participation in Vietnam … you don’t put aside someone like that.”

While his platoon struggled to clear his name, Minichiello asked for help with another mission: to find those who were aboard the TWA85, to apologize.

August 8, 2009

By summer 2009, Charlene Delmonico had already retired more than 8 years ago after 35 years working as a flight attendant for TWA.

Out of nowhere, Delmonico received an invitation. Would you be willing to meet the man who once pointed a gun at his back ?

The invitation came from Otis Turner and other platoon members of Raffaele.

Delmonico reacted in shock. The kidnapping had defined and changed his life. Why should she meet the man who had threatened her?

His second reaction, as a religious woman, was different. “I thought: they taught us to forgive . But I didn’t know how I would receive it,” he told the BBC.

In August 2009, Delmonico crossed the nearly 240 km that separated his home from Branson, in Missouri, where Minichiello and his platoon partners made the meeting.

There he met with Wenzel Williams, co-pilot of TWA85, who was the only other person to accept Minichiello’s offer. Cook refused, something that hurt the former kidnapper, who believed he had developed a bond with the captain.

In a room at the Clarion Hotel, Williams and Delmonico sat at a round table next to the squadmates but without Minichiello .

They presented them with a letter saying what they hoped to achieve with the meeting.

The support they provided to Minichiello convinced Delmonico that this was a man worth fighting for.

After a while, Minichiello arrived and sat at the table. The atmosphere remained tense. But as the questions began to arise, and Minichiello began to explain what had happened to him, the tension eased.

Minichiello seemed different to Williams: smaller and with a soft talk. He seemed to feel the weight of guilt when he revived the kidnapping. His regret seemed sincere.

“Somehow it was a closure, I heard a different point of view,” says Delmonico. “I probably felt sorry for him. I thought he was very kind. But he was always kind.”

Before leaving, Minichiello handed both a copy of the New Testament.

Inside he had written:

Thank you for your time, thank you very much.

I appreciate that you have forgiven my actions that put you in danger.

Please accept this book that has changed my life.

God bless you very much, Raffaele Minichiello.

Below, he added the words Luke 23:34 .

The passage says: “Father, forgive them, because they don’t know what they are doing.”

What happened after?

Raffaele Minichiello divides his time between the state of Washington and Italy, flies on a home plane for fun and has a YouTube channel dedicated to accordion music.

His platoon is still campaigning for him. As long as they cannot change the terms of their discharge, they will not be able to receive treatment for post-traumatic stress or other benefits that veterans enjoy.

Minichiello refused to be interviewed for this report because he signed a provisional agreement to make a film about his story.

According to his obituary, Captain Donald Cook “made his last flight to the afterlife on September 30, 2012, after a long and brave battle against cancer”

Charlene Delmonico – now Charlene Delmonico Nielsen – retired from TWA on January 1, 2001 after 35 years in the company. Missouri lives on.

The stewardess Tracey Coleman wrote to Minichiello while in prison, but is believed to quit his job at TWA two years after the kidnapping. His whereabouts are unknown.

Co-driver Wenzel Williams is retired and they live in Fort Worth, Texas.

Harpers Bizarre disarmed in the mid-70s. Dick Scoppettone has a program on the local radio in Santa Cruz, California.

In December 1972 , after kidnappers demanded a rescue and threatened to crash a plane into a nuclear plant, the Nixon government finally introduced security measures at airports , including electronic scanners of all passengers.

He blamed a “new type of kidnappers … unmatched in his cruelty.”

Source: Elcomercio